We have been working on designing new UX for one of our products. Obviously I had no idea on how to design good UX, hence I decided to level up by reading the Laws of UX: Using Psychology to Design Better Products & Services by Jon Yablonski.

Who is this book for?

This is one of the first books you should read if you are designing an interface that your customers will interact with. This includes UX designers, Product Managers, Product Designers etc. This book will add value to Product Engineers as well.

Usual Disclaimer

This post is by no means a summary of the book, the notes mentioned here are extracts from the book. If you find these interesting, please pickup a copy of the book and give it a go.

Jakob's Law

Users spend most of their time on other sites, and they prefer your site to work the same way as all the other sites they already know.

Users will transfer expectations they have built around one familiar product to another that appears similar.

By leveraging existing mental models, we can create superior user experiences in which the users can focus on their tasks rather than on learning new models.

When making changes, minimise discord by empowering users to continue using a familiar version for a limited time.

The less mental energy users have to spend learning an interface, the more they can dedicate to achieving their objectives. The easier we make it for people to achieve their goals, the more likely they are to do so successfully.

One of the primary ways designers can remove friction is by leveraging common design patterns and conventions in strategic areas such as page structure, workflows, navigation, and placement of expected elements such as search.

A mental model is what we think we know about a system, especially about how it works. Good user experiences are made possible when the design of a product or service is in alignment with the user's mental model.

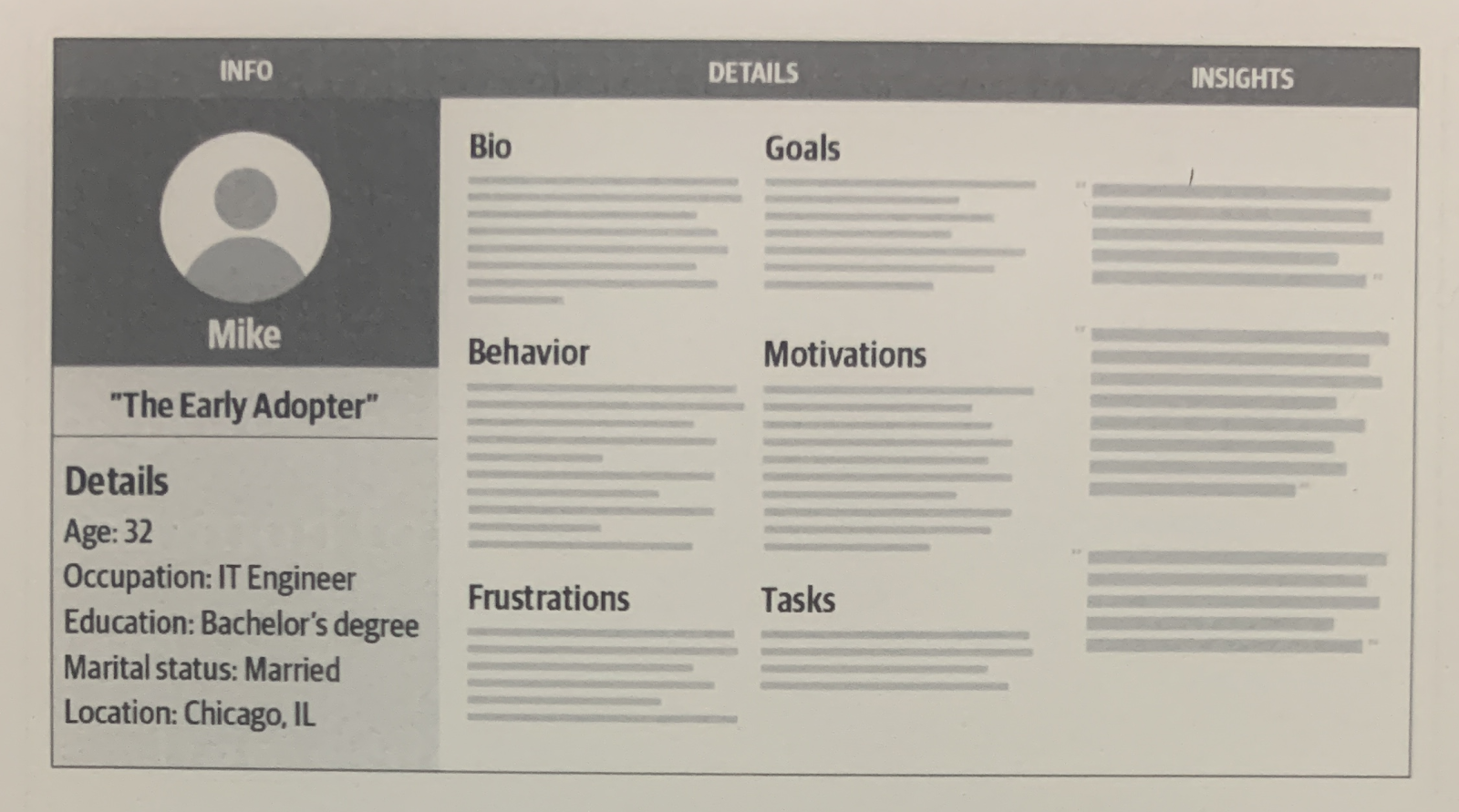

The process of design becomes more difficult when a design team lack a clear definition of its target audience, leaving each designer to interpret it in their own way. User personas are a tool that helps solve this problem by framing design decisions based on real needs, not the generic needs of the undefined "user".

The items common to most personas include:

- Info: Items such as a photo, memorable tagline, name, age and occupation.

- Details: This section helps to build empathy and align focus on the characteristics that impact what is being designed.

- Insights: This section helps to frame the attitude of the user. It helps further definition of the specific persona and their mindset.

Fitts's Law

The time to acquire a target is a function of the distance to and size of the target.

Touch targets should be large enough for users to accurately select them.

Touch targets should have ample spacing between them.

Touch targets should be placed in areas of an interface that allow them to be easily acquired.

As the size of an object increases, the time to select it goes down. Additionally, the time to select an object decreases as the distance that a user must move to select it decreases.

The touch targets should be large enough that users can easily discern them and accurately select them. Touch targets should have ample space between them. Touch targets should be placed in areas of an interface that allow them to be easily acquired.

According to research, people prefer to view and touch the centre of the smartphone screen, and that is where accuracy is the highest.

Hick's Law

The time it takes to make a decision increases with the number and complexity of choices available.

Minimise choices when response times are critical to increase decision time.

Break complex tasks into smaller steps in order to decrease cognitive load.

Avoid overwhelming users by highlighting recommended options.

User progressive onboarding to minimise cognitive load for new users.

Be careful not to simplify to the point of abstraction.

Complexity extends beyond just the user interface; it can be applied to processes as well. The absence of a distinctive and clear call to action, unclear information architecture, unnecessary steps, too many choices or too much information - all of these can be obstacles to users seeking to perform a specific task.

It's also important to consider when simplification can negatively affect the user experience - more specifically , when we simplify to the point of abstraction, and it's no longer clear what actions are available, what the next steps are, or where to find specific information.

Miller's Law

Don't use the "magical number seven" to justify unnecessary design limitations

Organise content into smaller chunks to help users process, understand, and memorise easily.

Remember that short-term memory capacity will vary per individual, based on their prior knowledge and situational context.

Human short-term memory is limited, and chunking helps us retain information more effectively. When we chunk content in design, we are effectively making it easier to comprehend. Users can then scan the content, identify the information that aligns with their goals, and consume that information to achieve their goals more quickly.

Postel's Law

Be empathetic to flexible about, and tolerant to any of the various actions the user could take or any input they might provide.

Anticipate virtually anything in terms of input, access and capability while providing a reliable and accessible interface.

The more we can anticipate and plan for in design, the more resilient the design will be.

Accept variable input from users, translating that input to meet your requirements, defining boundaries for input, and providing clear feedback to the user.

Anyone, regardless of device size, feature support, input mechanism, assistive technology, or even connection speed, should be served something that works.

The more fields you require users to fill out, the more cognitive energy and efforts you're asking of them, which can lead to a deterioration in the quality of the decisions made - decision fatigue.

Peak - End Rule

Pay close attention to the most intense points and the final moments (the "end") of the user journey.

Identify the moments when your product is most helpful, valuable, or entertaining and design to delight the end user.

Remember that people recall negative experiences more vividly that positive ones.

Instead of considering the entire duration of the experience, we tend to focus on an emotional peak and on the end, regardless of whether those moments where positive or negative.

Cognitive biases are systematic errors of thinking or rationality in judgement that influence our perception of the world and our decision-making ability. We attempt to preserve our existing beliefs by paying attention to information that confirms those beliefs and discounting information that challenges them. This is know as confirmation bias: a bias of belief in which people tend to seek out, interpret, and recall information in a way that confirms their preconceived notions and ideas.

The peak-end rule is related to another cognitive bias known as the recency effect, which states that items near the end of a sequence are the easiest to recall.

Journey mapping is invaluable for visualising how people use a product or service through the narrative of accomplishing a specific task or goal.

Journey maps usually contain some key information:

- Lens: It establishes the perspective of the person the experience represents. It usually will contain the persona of the end user, which should be predefined based on research on the target audience of the product or service. The lens should capture the specific scenario that the journey map is focused on.

- Experience: This section illustrates the actions, mindset and emotions of the end user mapped across a timeline. Typical information captured includes general thoughts, pain points, questions or motivations that originate from research and user interviews. Finally, there's the emotional layer, which is usually represented as a continuous line mapped across the entire experience and which captures the emotional state of the persona during the experience.

- Insights: This section identifies the important takeaways that surface within the experience. It usually contains a list of possible opportunities to improve the overall experience. It also contains a list of metrics associated with improving the experience, and details on the internal ownership of these metrics.

It is inevitable that at some point in the lifespan of a product or service something will go wrong. These types of situations can have an emotional effect on the people that use your product and may ultimately inform their overall impression of the experience.

Aesthetic-Usability Effect

An aesthetically pleasing design creates a positive response in people's brains and leads them to believe the design actually works better.

People are more tolerant of minor usability issues when design of a product or service is aesthetically pleasing.

Visually pleasing design can mask usability problems and prevent issues from being discovered during usability testing.

Contrary to what we've been taught not to do, people do in fact judge books by their covers. Automatic cognitive processing is helpful because it enables us to react quickly. Carefully processing every object around us would be slow, inefficient, and in some circumstances dangerous, so we begin to mentally process information and form an opinion based on past experiences before directing our conscious attention toward what we're perceiving.

The positive benefits of aesthetically pleasing design come with a significant caveat. Since people tend to believe that beautiful experiences also work better, they can be more forgiving when it comes to usability issues. Asking questions that lead participants to look beyond aesthetics can help to uncover usability issues and counter the effects that visual attractiveness can have on usability test results.

Von Restorff Effect

When multiple similar objects are present, the one that differs from the rest is most likely to be remembered.

Make important information or key actions visually distinctive.

Use restraint when placing emphasis on visual elements to avoid them competing with one another and to ensure salient items don't get mistakenly identified as ads.

Don't exclude those with a color vision deficiency or low vision by relying exclusively on color to communicate contrast.

Carefully consider users with motion sensitivity when using motion to communicate contrast.

In order to maintain focus on information that is important or relevant to the task at hand, we often filter out information that isn't relevant. It's a survival instinct know in cognitive psychology as selective attention, and it's critical not only to how we humans perceive the world around us but also to how we process sensory information in critical moments that could mean the difference between life and death.

Banner blindness describes the tendency for people to ignore elements that they perceive to be advertisements, and it is a strong and robust phenomenon that's been documented across three decades. We ignore anything that we don't typically find helpful. Instead, people are more likely to search for items that help them achieve their goals - especially design patterns such as navigation, search bars, headlines, links, and buttons.

Change blindness describes the tendency for people to fail to notice significant changes when they lack strong enough visual cues, or when their attention is focused elsewhere. Since our attention is a limited resource, we often ignore information we deem irrelevant in order to complete tasks efficiently. Because our attention is focused on what appears to be most salient, we may overlook even major differences introduced elsewhere. If it's important that the user be aware of certain changes to the interface of a product or service, we should take care to ensure that their attention is drawn to the elements in question.

Tesler's Law

Also known as the law of conservation of complexity, states that for any system there is a certain amount of complexity that cannot be reduced.

All processes have a core of complexity that cannot be designed away and therefore must be assumed by either the system or the user.

Ensure as much as possible that the burden is lifted from users by dealing with inherent complexity during design and development.

Take care not to simplify interfaces to the point of abstraction.

A key objective for designers is to reduce complexity for the people that use the products and services we help to build, yet there is some inherent complexity in every process. Inevitably we reach a point at which complexity cannot be reduced any further but only transferred from one place to another. At this point, it finds its way either into the user interface or into the processes and workflows of designers and developers.

When an interface has been simplified to the point of abstraction, there is no longer enough information available for user to make informed decisions. In other words, the amount of visual information presented has been reduced in order to make the interface seem less complex, but this has led to a lack of sufficient cues to help guide people through a process or to the information they need.

Doherthy Threshold

Productivity soars when a computer and its users interact at a pace (< 400 ms) that ensures that neither has to wait on the other.

Provide system feedback within 400 ms in order to keep users' attention and increase productivity.

Use perceived performance to improve response time and reduce the perception of waiting.

Animation is one way to visually engage people while loading or processing is happing in the background.

Progress bars help make wait times tolerable, regardless of their accuracy.

Purposefully adding a delay to a process can actually increases its perceived value and instill a sense of trust, even when the process itself actually takes much less time.

While a 100 ms response feels instantaneous, a delay of between 100 and 300 ms begins to be perceptible to the human eye, and people begin to feel less in control. Once the delay extends past 1000 ms, people begin thinking about other things; their attention wanders, and information important to perform their task begins to get lost, leading to an inevitable reduction in performance. The cognitive load required to continue with the task increases as a result, and the overall user experience suffers.

In some cases the amount of time required for processing is longer than what is prescribed by the Doherty threshold (> 400 ms), and there simply isn't much that can be done about it. But that doesn't mean we can't provide feedback to users in a timely fashion while the necessary processing is happening in the background. This technique helps to create the perception that a website or an app is performing faster than it actually is.

One common example used by platforms such as Facebook is the presentation of a skeleton screen when content is loading. This technique makes the site appear to load faster by instantly displaying placeholder blocks in the areas where content will eventually appear. The blocks are progressively replaced with actual text and images once they are loaded.

Another way to optimise load times is known as the "blur up" technique. This approach focuses specifically on images, which are often the main contributor to excessively long load times in both web and native applications. It works by first loading an extremely small version of an image and scaling it up in the space where the larger image will eventually be loaded. A Gaussian blur is applied to eliminate any obvious pixelation and noise as a result of scaling up the low-resolution image.

Animation is yet another way to visually engage people while loading or processing is happening in the background. A common example is "percentage-done progress indicators", also known as progress bars. Research has shown that simply seeing a progress bar can make wait times seem more tolerable, regardless of its accuracy.

Ten seconds is the commonly recognised limit for keeping the user's attention focused on the task at hand - anything exceeding this limit, and they'll want to perform other tasks while waiting. When wait times must extend beyond the maximum of 10 seconds, progress bars are still helpful but should be augmented with an estimation of the time remaining until completion and a description of the task that is currently being performed.

Another clever technique for improving perceived performance is the optimistic UI. It works by optimistically providing feedback that an action was successful while it is being processed, as opposed to providing feedback only once the action has been completed. For example, Instagram displayed comments on the photos before they are actually posted. It only displays an error afterward in the event that the action isn't successful.

It might seem counterintuitive, but it's important to also consider when response times might be too fast. When the system responds more quickly than the user expects it to, a few problems can occur. First, a change that happens a little too fast may be completely missed. Another issue that can occur is that it can be difficult for the user to comprehend what happened, since the speed of change does not allow sufficient time for mental processing. Finally, too-fast response time can result in mistrust if it doesn't align with user's expectations about the task being performed. Purposefully adding a delay to a process can actually increase its perceived value and instill a sense of trust, even when the process actually takes much less time.

With Power Comes Responsibility

Random reinforcement on a variable schedule is the most effective way to influence behaviour. Digital platforms can also shape behaviour through the use of variable rewards, and this can be observed each time we check our phones for notifications, scroll through a feed, or pull to refresh.

Infinite loops like autoplay videos and infinite scrolling feeds are designed to maximise time on site by removing friction. Without the need for the user to make a conscious decision to load more content or play the next video, companies can ensure that passive consumption on their sites or apps continues uninterrupted.

We humans are inherently social creatures. The drive to fulfil our core needs for a sense of self-worth and integrity extends to our lives on social media, where we seek social rewards. Each "like" or positive comment we receive on content we post online temporarily satisfies our desire for approval and belonging. Such social affirmation delivers a side dish of dopamine.

Default settings matter when it comes to choice architecture because most people never change them. These settings therefore have incredible power to steer decisions, even when people are unaware of what's being decided for them.

Remove as much friction as possible - The easier and more convenient you make an action, the more likely people will be to perform that action and form a habit around it.

Reciprocation, or the tendency to repay the gestures of others, is a strong impulse we share as human beings. It's a social norm we've come to value and even rely on as a species.

Dark patterns are yet another way technology can be used to influence behaviour, by making people perform actions that they didn't intend to for the sake of increasing engagement or to convince users to complete a task that is not in their best interest.

Ethics must be an integral part of the design process, because without this check and balance, there may be no one advocating for the end user within the companies and organisations creating technology. The corporate goals of the business and the human goals of the end user are seldom aligned, and more often than not designers are conduit between them. The first step in making ethical design is to acknowledge how the human mind can be exploited.

Applying Psychological Principles in Design

One of the most effective ways we can ensure consistent decision making within the design process is by establishing design principles: a set of guidelines that represent the priorities and goals of a design team and serve as a foundation for reasoning for decision making. They help to frame how a team approaches problems and what it values.

To define design principles follow these steps:

- Identify the team: First step is to identify the team members who will participate. A common approach is to keep things open to anyone who wishes to contribute. It may also be a good idea to open the process to design leadership and stakeholders outside of immediate team.

- Align and define: It's time to carve out some time and kick things off by first aligning on success criteria. This means not only creating a shared understanding of design principles and the purpose they serve, but also defining the goals of the exercise.

- Diverge: The next step is commonly centred around idea generation. Each team member is asked to brainstorm as many design principles as they can for a defined amount of time.

- Converge: Next step is to bring all those ideas together and identify themes participants are usually asked during this phase to share their ideas with the group and to organise those ideas according to themes that surface during the exercise. Then they are asked to vote on the themes they feel are most appropriate for the team and the organisation.

- Refine and apply: It's common to first undergo a refinement stage and then identify how the principles can be applied. It's a good idea to identify where and how these principles can be applied within the team and the organisation as a whole.

- Circulate and advocate: The final step is to share the principles and advocate for their adoption. Circulation can come in many forms: posters, desktop wallpapers, notebooks, and shared team documentation are all common mediums. It's critical that team members who participated in the workshop advocate for these principles both within and outside the team.

The following are the few best practices to help ensure the design principles your team adopts are useful:

- Good design principles aren't truisms: They are direct clear and actionable, not bland and obvious.

- Good design principles solve real questions

- Good design principles are opinionated: They should have a focus and a sense of prioritisation, which will push the team in the right direction when needed and drive them to say no when necessary.

- Good design principles are memorable: If they are hard to remember they would be less likely to be used. They should feel relevant to the needs and ambitions of the team and the organisation as a whole.

Conclusion

This is an awesome book that list down most common principles to follow when designing any interface. It is also short and crisp, you wont spend months reading it. I would recommend reading this book for anyone working towards building a product!